Much of what currently passes as interdisciplinary work in computational creativity is profoundly lacking in artistic experience and understanding. This is a pervasive and critical flaw — after all, the creative side of the equation is our primary goal, is it not?

To help us consider a more appropriate balance, let’s briefly examine how human composers and analysts approach their work.

Music as Data

Our first challenge is that musicians don’t generally think of raw musical materials as data. Immediately we find a conflict between the computational and creative — how can we compute without data? The answer lies with how we collect, represent, and ultimately select musical elements for processing. The key issue we need to consider is context.

Interpreting the musical context around individual events is what allows us to develop a meaningful picture of how groups of musical events function. Understanding these musical effects requires computational systems to make aesthetic judgments based on experience (or training in this case). I’m developing my own approaches to this set of challenges, but suffice it to say…

Any composer that deals with musical materials as anything but a means to achieve musical effect is not likely to produce results worth exploring or repeating.

A Composer’s View

Composers seek combinations of musical patterns that take on an irrepressible life of their own. As someone with decades of experience attempting this, I can say that it’s an intimate and perilous journey with few external guiding references. Every step forward simultaneously removes options and presents new opportunities, and when a combination of musical events expressing strong potential finally presents itself, there are no guarantees.

Unfortunately, this first-hand description of the compositional process isn’t very helpful when designing creative algorithms. To do that, we need ways of defining and comparing the effect of musical ideas to learn what sinks and what floats. In recent years my work as composer, pianist, and researcher has focused on developing a computation-friendly approach to this problem and I believe reasonable solutions aren’t that far off.

What About the Analyst?

On the other hand, analysis (whether computational or theoretical) encourages the deconstruction and justification of existing musical ideas by developing a highly-relational network of connections between events with clearly definable attributes. Strange as it may seem, some of these relationships may be carefully planned and executed by the composer, but many are not.

Ultimately, analysis aims to reveal a tightly woven fabric of methodically cataloged connections; regardless of the composer’s design or intent, and without the natural aesthetic judgments mandated by the compositional process.

Analysis is a necessary component of model-based computational composition. But for analysis to become directly relevant to the compositional process, it must be capable of addressing a wide range of emotional potential to provide a meaningful musical experience. In other words, it must evolve to encompass the pleasures that music provides to us.

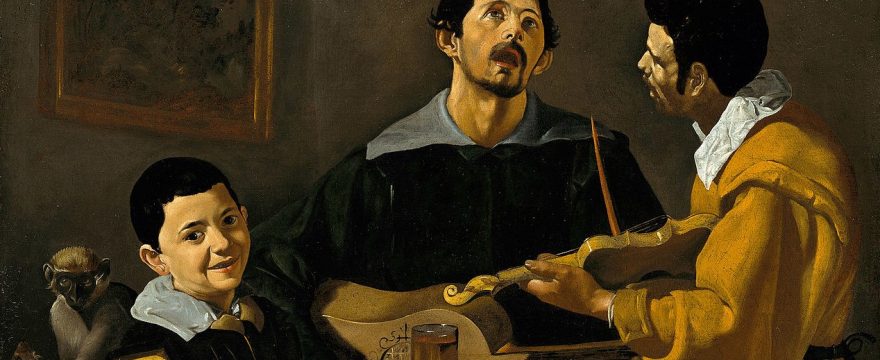

Pleasures of Music

What exactly do I mean by the “pleasures” of music?

Well, I don’t mean the types of emotional associations that attach themselves to musical textures, forms, and ideas through cultural conditioning and repetition. No. I’m speaking of an aurally perceptible, inner geometry that attaches itself to our collective nervous system and forces us to repeat and examine it for generations upon generations.

While it may be difficult to codify them, these designs are recognizable and valued because we are human. We find a pleasure in their architecture that universally speaks to us, regardless of time and cultural distance. And they did not come to exist in a vacuum — they have been under constant development for thousands of years through the myriad generations that precede us. Lucky for us, these designs can be found throughout the musical canon.

To create music worthy of sustained exploration and repetition, computational creativity must seek out the patterns and trends that elucidate these universal pleasures. This process begins with our attempting to understand fundamental musical aspects like memory, identity, expectation, surprise, and developing a data-driven understanding of the expressive qualities of musical character.